Many programmers are struggling with questions such as:

- what are the rules for naming a variable, class or a function?

- what are the variable naming conventions in Python, JavaScript or any other language?

- how to name a class or how to name a class method in Java or any other object-oriented language?

In fact, naming things in programming to convey its meaning in a precise fashion is an arduous task, often requiring much thought and years of experience. But fret not – if you are an aspiring software developer, this skill will bring you a lot of value working with other developers on smaller and bigger projects.

How to read this article

This article is divided into two chapters.

- The first one, starting with section “Introduction to naming in programming” presents a review of scientific literature present on the topic. That section will deepen your understanding of the current body of knowledge on naming things.

- The second chapter, starting with section “Guidelines for naming conventions in programming” presents actionable recommendations to improve your skills in choosing thoughtful class, function or variable names. If you’re looking for tips, go there.

Chapter 1. Introduction to naming in programming

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.

Phil Karlton

Naming is an essential but grossly underrated skill. Every programmer faces the problem of finding good names on a daily basis. According to one study which analyzed Eclipse source code, about 70% of code is made up of names [1]. Caprile et al. state that “identifier names are one of the most important sources of information about program entities” [2]. Hence, good naming is necessary for the code to be readable and maintainable ( imagine trying to understand a program in which identifiers were replaced with random strings). Yet, few programming textbooks and university courses discuss the topic beyond a few syntactic do’s and don’ts. Vague rules such as “identifiers should be self-describing” are not explained and are hard to follow, especially for novices. Ironically, studies show that beginners are especially reliant on good names, as more experienced developers are better at reading contextual cues [3]. Moreover, ‘given the importance of identifier naming, several research projects have considered the issue of identifier naming conventions. Naming conventions are important because “studies of how people name things (in general not just in code) have shown that the probability of having two people apply the same name to an object is between 7% and 18%, depending on the object” [4].’ While developers agree that naming matters, they adhere to different conventions and disagree on critical aspects such as acceptable names lengths. Very few use written guidelines or consult empirical evidence.

This article aims to discuss the results of the psychological research on naming and present a summary of naming guidelines based on current literature and the author’s own experience. It’s also meant to be used as a reference to help improve code style and inform code reviews. The Markdown version (without the introduction) is available at the bottom of the article. We also provide references and further reading.

What is naming in programming?

In the context of computer programming, naming is the act of assigning identifying labels to programmatic constructs. It can be conceptualized as a process of expressing meaning or purpose as concisely and unambiguously as possible without revealing the underlying implementation. However, unlike in natural languages where speakers share a vast, mutually understood, but fairly fixed lexicon, naming in programming makes the intensive use of invented words. Liblit et al. point out that “compilers have no understanding of natural language, so “blue” and “Sgu9Asd1M” are equally opaque, arbitrary sequences of letters. Provided that the programmer uses consistent spelling and capitalization, any name is as good as any other. Yet precisely because names are arbitrary, programmers have great freedom to select names that promote code understanding. [6]”

Research into the cognitive processes that underlie language and text comprehension shows that the semantics of words is key to understanding [1]. In other words, names guide the psychological processes of understanding the code. Arnaoudova et al. explain: ‘In his theory about program understanding, Brooks considers identifiers and comments as part of the internal indicators for the meaning of a program. Brooks presents the process of program understanding as a top-down hypothesis-driven approach, in which an initial and vague hypothesis is formulated — based on the programmer’s knowledge about the program domain or other related domains — and incrementally refined into more specific hypotheses based on the information extracted from the program lexicon. While trying to refine or verify the hypothesis, sometimes developers inspect the code in detail, e.g., check the comments against the code. [5]’

Meaning and structure of names in programming

Naming is a form of communication, be it between the author and herself or between the author and other programmers. The goal of a name is to communicate the author’s intent, the behaviour of something (name’s referent), its usage, significance, role or concept. Bad names obviously make the dialogue harder, but how good names convey meaning? In general, we deal with two types of entities: objects* and functions. In the case of objects, the problem is straightforward; we use a noun and optionally an adjective:

device_storage

proxy_manager

database_connection

failed_requestA function name, on the other hand, stands for a group of statements to be executed (in imperative languages) or a composition of expressions (in functional languages) to be evaluated. Therefore, the name will express the implied action, side-effect or value by including a verb — “do this!”. This is the case even in purely functional languages such as Haskell. Typically, a name will use the imperative mood with the second-person subject (e.g. calculateNumberOfCars), so the general form is a verb plus optional object.

sleep(…)

retry_request(…)

setup_db_connection(…)Typically there is little reason to deviate from this form, but there are, of course, exceptions, such as names of callbacks, e.g. on_widget_loaded, boolean functions — is_user_authorized of transformations — to_binary. However, even in those cases, the verb is often implied as we can see in previous examples: (do)_on_widget_loaded, (check)_is_user_authorized, (convert)_to_binary.

Caprile and Tonella, based on the analysis of a few large open-source code-bases, defined a formal grammar describing function identifiers. In it, they identified six main name forms [7]:

- indirect action, e.g. error() or on_error()

- direct action, e.g.open(), close(), kill()

- action on object, e.g. read_line(), open_file()

- double action, e.g. search_and_replace_text()

- property check, e.g. is_active() or active()

- transformation, e.g. convert_to_hex()

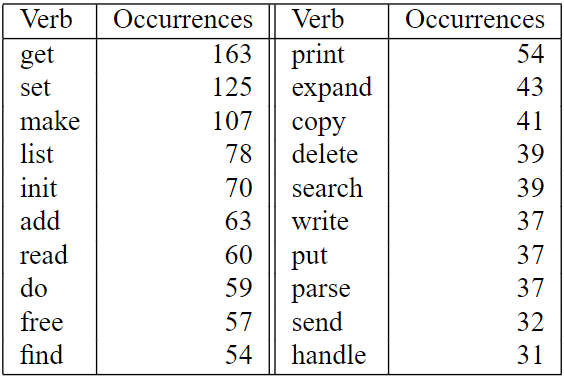

The following table, taken from the paper, illustrates the number of occurrences for the top twenty verbs used in bash’s source code:

Concision – on long and short variable and function names

Names are layers of indirection, separating essential features of what things are, or what they do, from the unnecessary details. They work very similarly to interfaces or abstract types in that their primary role is to express an abstract concept. “Layers of indirection can be peeled away incrementally, allowing us to work within a codebase without understanding its entirety. Without indirection, we’d be unable to write software longer than a few hundred lines.” [8] A perfectly concise name expresses the concept that needs to be understood by the reader, nothing more, nothing less. Revealing (or leaking) implementation is not only harmful because it leads to tight coupling, but it can also make the meaning harder to grasp. Let’s consider the following example:

val age: int = 7

val integer: int = 7The second name is precise and technically correct but also meaningless. Yes, the value of a variable is an integer, but what is its purpose? Let’s consider another example:

val blowfish = getCypherFunction(algorithm = BLOWFISH)The further we get from this line of code, the higher the risk that someone may be confused by the variable’s name if she doesn’t know that blowfish is a cypher. Probably “cypherFn” or “cypherFunction” would be a better alternative — this one is too specific.

Another aspect of conciseness is length. Unsurprisingly, studies show that single-letter abbreviations are terrible for comprehensibility, and longer names are better, but up to a point. Names that are too long can crowd a programmer’s short-term memory.

“The study […] shows that better comprehension is achieved when full-word identifiers are used rather than short (virtually) meaningless identifiers. It also shows that in many cases abbreviations are just as useful as the full-word”. [9]

On the other hand, it is more difficult to read and remember long variable names. This, in turn, suggests that software engineers are more productive when they can minimize the length of identifiers while preserving the use of full-words or carefully choosing abbreviations. Extraneous characters which increase the length of an identifier (e.g., “its” in the attribute “itsHeight” or the use of Hungarian notation) make recall harder. Binkley at al. point out that “statistical models derived from an experiment involving 158 programmers of varying degrees of experience show that longer names extracted from production code take more time to process and reduce correctness in a simple recall activity” and that “maximal comprehension occurs when the pressure to create longer more expressive names is balanced against limited programmer short-term memory.” [10]

In general, if it’s difficult to express the meaning in a few words it probably means that we have a problem with our program’s structure and should break something down into smaller components. For example, function findArticlesWithoutTitlesThenApplyDefaultStyles should be broken down into findArticlesWithoutTitles and applyDefaultStyles. Similarly, functions such as:

isCurrentSquareNextToAtLeastOneBlockedSquare()

searchBlockedListForBlockedSquares()could be broken into following methods:

currentSquare.nextToBlockedSquare()

blockedList.getBlockedSquares()In general, if there’s a shorter but descriptive way to name the entity, then the name is too long and if the name is not easily reducible, then there’s probably a problem in technical design.

Unambiguity

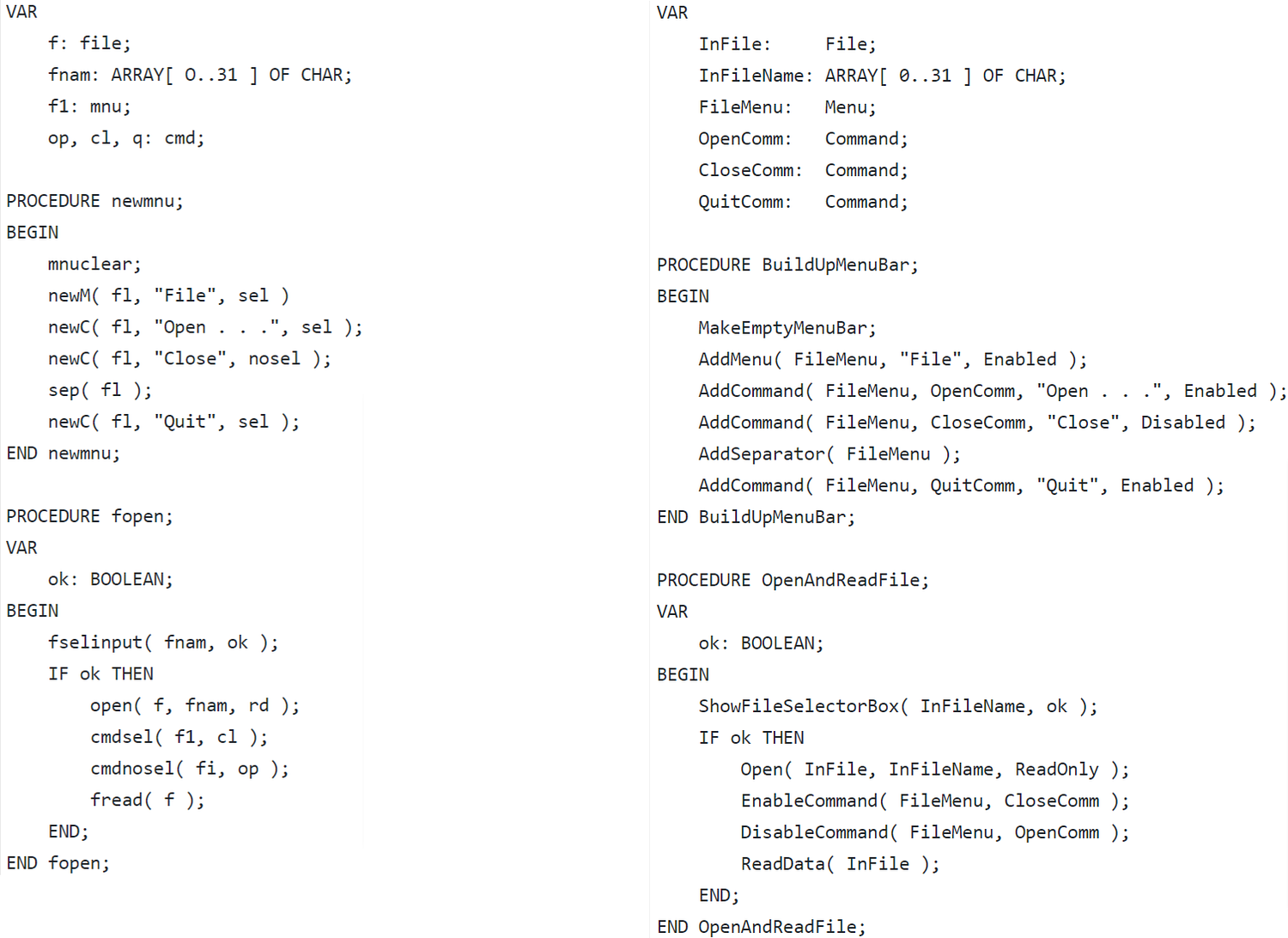

As we saw, one source of ambiguity are names that are too specific or too general. Other common problems include abbreviations, homonyms and synonyms. Studies clearly show that abbreviations negatively impact code comprehensibility. Compare the following two code fragments:

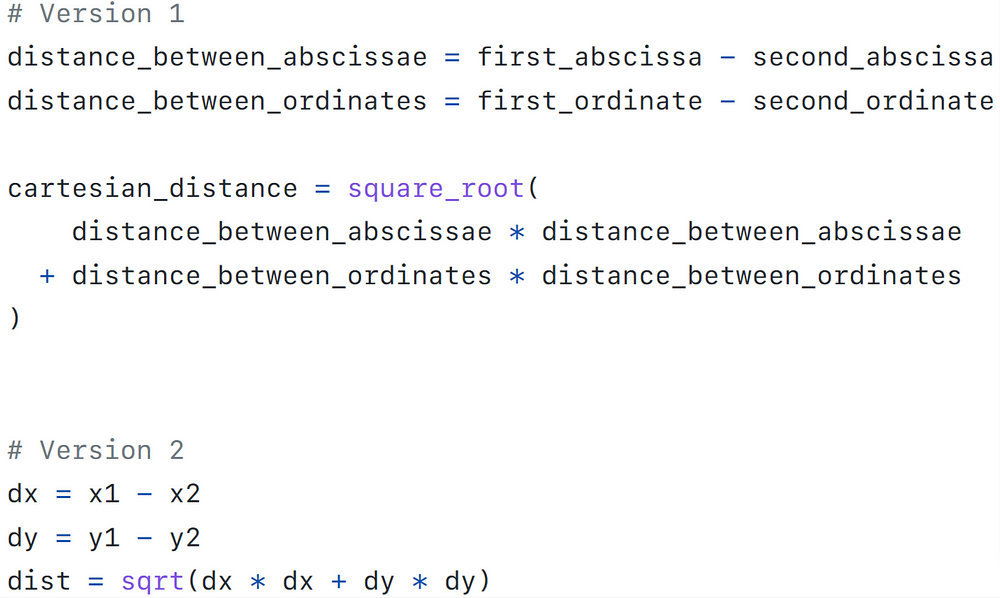

Only exceptions to this are abbreviations that are very well known or pretty much universal, such as auth, id, or sqrt. Some languages have specific abbreviations which are pretty much reserved, such as m for map and k for key in Clojure, so there is little reason for confusion, except for novices. In the following example, which takes advantage of well-established mathematical conventions, the abbreviated version is clearly more readable:

What about one-letter indices? Indices such as i or j, are reasonably well-known, especially in languages that heavily use traditional loops, such as C. However, in modern languages, there is usually little reason to use them over higher-order functions such as map, forEach or for <name> in <collection>, which avoid indices altogether. Moreover, even though it should be immediately apparent that i and j are indices, it’s still very easy to mix them up because two letters are so similar to each other.

Homonyms are words with multiple meanings, such as “bark”, “die”, or “spring”. Studies on comprehension of ambiguous sentences resulting from the presence homonyms have shown that readers who encounter homonyms experience slower comprehension. This is due to the mentally activiting various meanings of words [14].

The problem is especially subtle in programming because we rarely encounter homonyms from entirely different domains such as for a word “current”, which normally means “belonging to the present time”, not “a body of water or air moving in a definite direction”. More likely, a source of confusion are names which by convention can refer to multiple different things such as “file”, which can mean file handle, filename, file path or simply contents of the file.

Synonyms are problematic when the same objects are inconsistently named in different places with different synonyms, such as using “cluster” in one place and “group” in another. The reader won’t be sure whether the names refer to the same thing. This usually comes up when different programmers work in parallel on the same features and choose distinct names (which happens often).

Formal model

Deissenboeck and Pizka defined a formal model to express and validate precisely what does it mean for a name to be correct, consistent and concise [1]. In their model, greatly simplifying, they recognize concepts, names for the concepts, program entities and identifiers of program entities. Within the model, consistency (lack of synonyms and homonyms) means that there is a 1:1 correspondence, i.e. unique relation, between concept names and concepts themselves. On the other hand, correctness means that the identifier of a program entity that manifests a concept must correspond to the unique name of the concept or one of more general concepts. This rule makes sure that identifier names don’t become completely meaningless or incorrect. Let’s take, for example, a function called p, which returns a permutation of a set of elements. Because p is neither the name of the concept of permutation nor of a generalization of it, the identifier violates the correctness rule. A wrong identifier, such as load, would also be disqualified. However, correctness is not enough to make transformation an invalid identifier. It corresponds to the name of a generalization of the concept, but it is only of limited assistance for the reader. This is a very common problem: identifiers are often correct, but not concise enough [1]. Conciseness, therefore, requires that an identifier has exactly the same name as the concept it stands for, no generalizations allowed. In our example, only permutation would be a correct and concise name for the function p.

In summary, a name can be:

- Too specific

- i.e. overspecifying/leaking implementation

- i.e. too long or consisting of too many words to read at a glance

2. Too ambiguous

- i.e. expressing a too generic concept

- i.e. being a homonym (have multiple meanings)

- i.e. an abbreviation that is unobvious

3. Incorrect, i.e. expressing the wrong concept

4. Inconsistent, i.e. expressing already-named concept using a different name

Why is naming hard?

One reason for poor naming may be related to the hindsight bias — the “curse of knowledge” [12]. It’s a phenomenon where people already with the knowledge of something have a hard time imagining they don’t possess it. When you’re an expert, something that is hard and unobvious for your less-experienced colleagues seems trivial to you, which leads to a handicap in estimating the difficulty the novices will face.

In the context of naming, this may lead to a situation where the name seems good at the time because the programmer has all the contextual knowledge fresh in their working memory. However, the name is only tested when the reader has to use it for cueing memory retrieval or for guiding new memory formation. In other words, we are destined to be poor judges of our own names. When writing the code, most esoteric abbreviations and most generic names will seem evident because we already know what they mean. One solution to this problem is, of all things, compassion. Always ask yourself: “would a junior programmer understand this?”.

Deissenboeck and Pizka also point out that “amongst others, there are three important reasons for the inappropriate naming of identifiers encountered in numerous codebases:

- Identifiers can be arbitrarily chosen by developers and elude automated analysis.

- Developers have only limited knowledge about the names already used somewhere else in the system.

- Identifiers are subject to decay during system evolution. The concepts they refer to are altered or abandoned without properly adapting the names. One reason for this is the lack of tool support for globally renaming sets of identifiers referring to the same concept.

Due to 3 naming deficiencies can not solely be explained as a result of neglect by careless programmers. It is indeed practically impossible to preserve globally consistent naming during long-term development efforts, maintenance, or evolution without additional tools. Note, in contrast to a rather simpler name refactoring all identifiers names referring to a concept must be found and renamed consistently each time the concept itself changes. [1]” Finally, as we said earlier, the probability of having two people apply the same name to an object is very low.

Chapter 2. Guidelines for naming conventions in programming

Below, we present a summary of naming guidelines based on current literature, specifically a catalogue of linguistic antipatterns proposed by Arnaoudova et al. [13] and guidelines compiled by Hilton [14] and us. The relevance of some rules depends on the paradigm or community consensus, which should, in general, override any rules posted here.

1. Syntax

1.1 Be consistent

Consistency in naming makes reading and memory retrieval much, much easier. Conversely, changing rules and mixing conventions are very confusing and significantly increase cognitive load. Follow language, company, and project conventions for names, even if you don’t like them.

1.2 Follow conventions

Most programming languages have stylistic conventions for writing names – if not official, most communities provide their own. Use language-specific code linters to check the code.

1.3 Use dictionary words

Only use words and abbreviations that are in the dictionary. Use abbreviations and acronyms only if everyone knows what they mean. Make exceptions for abbreviations such as id and other well-known or documented domain-specific abbreviations. Names can become confusing if spelling errors are made, especially inconsistently. In general, abbreviations, if not well-known, add further ambiguity.

- Avoid neologisms and slang.

Use existing, well-known names, especially if your team is not all native English speakers. - Avoid letter-only names.

Especially single-letter names. Yes, this counts for loops too. Unless you’re using C, there is little reason for using manual loops anyway, as most languages support functional iteration.

for (Element element : elements) {

...

}

for (int i = 0; i < elements.size; i++) {

val element = elements[i];

...

}- Avoid esoteric abbreviations and acronyms.

Especially arbitrary ones you too will forget in five minutes. Example:

while(i_love_lucy_is_on_tv)

{

xqtc_fn();

}1.4 Make names pronounceable

This will make it easier for your brain to remember them.

- Avoid special symbols.

Make exception for_in snake case and other special conventions. For example,>=>and<*>are valid function identifiers in Scala, colloquially named fish and space ship. In Clojure,->function is a well-known “thread-first” macro (together with=>, “thread-last” macro”). - Only use underscores between words (and other symbols).

Example violation:_ans_var_question_05ortrivWndFeedback_. - Only use one underscore at a time.

Exception: In Python, double underscore indicates special method defined by the Python language, e.g.__init__.

1.5 Keep length within reasonable bounds

No hard rules here; use your good judgement. In general:

- Prefer full-words over abbreviations.

- Limit name word count (<= 4). Avoid unnecessary context and keep your name length to a maximum of four words. Names should be limited to the maximum number of words people can read at a glance.

- Limit character length. Keep name length within 20 characters.

- Non-reducible longer length name marks a problem in technical design in most cases. For example:

isCurrentSquareNextToAtLeastOneBlockedSquare(currentSquare)

// could be moved into a method (if using OOP):

currentSquare.nextToBlockedSquare()1.6 Make sure names are hard to mix up

- Make names differ phonetically.

Example:data_earthanddate_of_birth. - Make names differ by more than word order.

For example,employeeCountandcountEmployeesin the same lexical context would be very easy to mix up. - Don’t shadow existing names.

- Avoid numeric suffixes. Do not add numbers to multiple identifiers that share the same base name, e.g:

val employee1 = convert(employee)

val employee2 = convertSomeMore(employee1)1.7 Name constant values

Don’t rewrite a value as a name; name what the value represents. Replace number names with either domain-specific terms, such as PI, or a name that describes the concept that the number represents, such as BOILING_POINT. However, don’t define constants for values which don’t have names and/or are not special:

#define ONE_THIRD 0.252 Semantics

Make sure that a name is not:

- too specific

- overspecifying/leaking implementation

- too long or consisting of too many words to read at a glance

- too ambiguous

- expressing a too generic concept

- being a homonym (having multiple meanings)

- an abbreviation that is unobvious to a junior

- incorrect, i.e. expressing the wrong concept

- inconsistent, i.e. expressing an already-named concept using a different name.

2.1 Express meaning

- Use large vocabulary to avoid homonyms and synonyms.

filecan be replaced withfilename,filepath,fileContentsorfileHandle, according to it’s specific meaning. If you’re trying to express the concept of “perimeter”, use identifierperimeterinstead ofboundary. - At the same time, make sure you’re consistent in your naming and not using too exoteric words, especially if the team is not speaking English natively.

- Use problem domain terms.

Prefer terms which relate to the problem the software is solving or that the client is using.

2.2 Avoid ambiguity

- Be specific.

Avoid abstract and generic words like it, everything, data, handle, stuff, do, routine, perform. Examples:

func_1()

handle_data()

do_args_method()- Abbreviate with care.

As a rule of thumb, if you’re not sure if a junior in your team knows particular abbreviation, it’s a good idea to skip it. Also, watch whether the abbreviation is ambigous. Examples:

e // for error, event or element

cx // count of x

f // for flag

nbr // for number

tbl // for table- Use standard, neutral language.

killis better thandispatchorslay. - Use positive Boolean names.

PreferisEnabledoverisNotDisabled. - Use standard opposite pairs

Typical pairs include add/remove, begin/end, create/destroy, destination/source, first/last, get/release, increment/decrement, insert/delete, lock/unlock, minimum/maximum, next/previous, old/new, old/new, open/close, put/get,show/hide, source/destination, start/stop, target/source, and up/down. - Make names differ in meaning

Names like input andinputValue, andrecordCountandnumberOfRecordscan be easily confused if used in the same lexical context:

val recordCount = ...

...

val numberOfRecords = ... // Huh? We have this already2.2 Don’t leak implementation

The name should express precisely what needs to be understood by the reader, nothing more. Avoid overspecifying meaning; treat names as kind-of generic interfaces – boil down the essence of what something is, identify and remove all that is not essential or can change. Leaking implementation is bad because it increases noise in the code and the coupling between different objects (in this case, between statements or expressions that use an overspecified term).

- Keep name’s meaning relevant to the semantics in its immediate context, nothing more. For example, if you’re working with in-memory key-value database such as Redis, then probably your business logic shouldn’t know all the details about its client object, such as that it is in-memory or Redis specficially. Then the

keyValueStorewould be a better name thaninMemoryKeyValueStoreorredisClient. - Omit type information, except for

isprefix for Booleans. Generally, it’s a good idea to avoid Hungarian like notations which leak the type of object, but the problem with Booleans such asisActiveis that “active” on its own can be confused with an adjective with an implied noun – “active something” instead of “is something active?”. Booleans don’t generally change types to non-Booleans, so it’s a safer and more readable option.

2.3 Ensure semantic correctness

isshould only return Boolean.

Methods starting withis, e.g.isActiveshould returntrueorfalse, nothing else, and should not produce side-effects.setmethod shouldn’t return anything.

Setter methods imply that their result is a side-effect (of setting some variable) – returning something is confusing and counter-intuitive.getshould return something.

By convention, getter methods should always return something. Example violation: methodgetImageDatasets the state of some global variable and doesn’t return anything.- Predicates should answer question.

Method names in form of a predicate (e.g.isEnabled) should return a Boolean, not anullor an object. Example violation: attributeisReachedof typeint[]where the declared type and values are not documented. - Use Boolean variable names that imply true or false.

If method or a variable is of Boolean type, its name should suggest so, e.g.isAuthorized(). - Don’t use

get,isorhasprefixes for functions with side-effects.

Those words don’t imply or suggest that side-effects can’t happen, so the reader cannot assume that they will happen. If they do, it will probably be surprising to the reader. - Transform method should return anything.

Example:apply_transformation_1(x)return return transformedx. - Method name and behavior should be consistent.

For example, the result of calling functiondisable(...)should be a side-effect of disabling something, not, for example, returning object or function which can disable something. - Attribute name and type should be consistent.

Example violation: attributestartObjectis of typeObjectEnd. - Match plurality.

If an attribute is of collection type, its name should reflect that, e.g.userNames: Set<String>instead ofuserName. Use plural nouns for function names which work on collections, e.g.convertDates(dates: List<Date>)instead ofconvertDateand return collections if name suggests so. - Don’t contradict comments. Keep them up to date.

GitHub Gist link:

https://gist.github.com/IwoHerka/a254cbfb2fadba5f240e68a16fc36c89

It’s nice to work with a team that uses scientific research to improve their craft, isn’t it?

Start by dropping us a lineReferences

-

a

b

c

d

e

Deissenboeck, Florian, and Markus Pizka. “Concise and consistent naming.” Software Quality Journal 14.3 (2006): 261–282.

-

^

Caprile, Bruno, and Paolo Tonella. “Restructuring Program Identifier Names.” icsm. 2000.

-

^

Lawrie, Dawn, et al. “Effective identifier names for comprehension and memory.” Innovations in Systems and Software Engineering 3.4 (2007): 303–318.

-

^

Feitelson, Dror, et al. “How developers choose names.” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering (2020).

-

^

Arnaoudova, Venera, Massimiliano Di Penta, and Giuliano Antoniol. “Linguistic antipatterns: What they are and how developers perceive them.” Empirical Software Engineering 21.1 (2016): 104–158.

-

^

Liblit, Ben, Andrew Begel, and Eve Sweetser. “Cognitive Perspectives on the Role of Naming in Computer Programs.” PPIG. 2006.

-

a

b

Caprile, C., and Paolo Tonella. “Nomen est omen: Analyzing the language of function identifiers.” Sixth Working Conference on Reverse Engineering (Cat. No. PR00303). IEEE, 1999.

-

^

Tellman, Z., 2019. Elements of Clojure. 1st ed. lulu.com.

-

^

Lawrie, Dawn, et al. “What’s in a Name? A Study of Identifiers.” 14th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC’06). IEEE, 2006.

-

^

Binkley, Dave, et al. “Identifier length and limited programmer memory.” Science of Computer Programming 74.7 (2009): 430–445.

-

John Anderson, J. R. “Cognitive psychology and its implications.” (1995).

-

^

https://towardsdatascience.com/the-curse-of-knowledge-8deb4769bff9

-

^

Arnaoudova, Venera, et al. “A new family of software anti-patterns: Linguistic anti-patterns.” 2013 17th European Conference on Software Maintenance and Reengineering. IEEE, 2013.

-

a

b

Hilton, Peter, and Felienne Hermans. “Naming Guidelines for Professional Programmers.” PPIG. 2017.

-

Green, Roedy, How To Write Unmaintainable Code – A more maintainable, easier to share version of the infamous http://mindprod.com/jgloss/unmain.html. GitHub. https://github.com/Droogans/unmaintainable-code#naming

As the Principal Software Engineer at Makimo, Iwo Herka thrives in the rich terrain of Elixir and functional programming. He employs a scientific approach to demystify its complexities, chronicling his findings in in-depth articles, insightful talks, and informative videos. When he steps away from the pulsating world of code, Iwo can be found trekking nature's trails or engrossed in a good book. For Iwo, programming isn't merely a job — it's a daily adventure he passionately embarks on.